Marvel Studios: The Unwilling US Foreign Policy Pundit

I’m embarrassed to share this: Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) films are some of the most intellectually engaging films to me. After each film, I’d spend days analyzing its commentary on US foreign policy. Like a TV detective stereotype, I’d compile evidence—comparing the plots of the comic book source material and the film. I’d circle the parts the film kept and the parts it discarded. With the interrogations interviews of Joss Whedon and the Russo brothers playing in the background on loop.

My forensic theory? Marvel Studios cannot help but condemn US foreign policy. Yet, the studio undercuts every serious critique by reducing structural problems to individual faults. Comic book writers and the global demand for Marvel drive the criticism, yet the US market and financiers tone down the dissent. MCU becomes a highly watered down lamentation of US foreign policy.

Marvel Studios has to comment on contemporary US foreign policy because the characters they inherited came with histories inextricably tied to the US military. They can’t set Captain America’s origin story in a fictional frozen Norwegian kingdom when his name is Captain, erm, America. Nor can they injure Tony Stark in a peaceful town instead of a war-torn foreign country he sells American weapons in. Marvel is hyper aware that what they do with Cap and Iron Man will be seen as commentary.

See a very American Captain America touring the US to spread war propaganda and sell War Bonds in the film.

See a very American Captain America touring the US to spread war propaganda and sell War Bonds in the film.

But why levy criticisms of US foreign policy rather than praise? The comic book origin of MCU is yet again a driving factor. Marvel inherits the progressive themes of the Marvel comics. Comics are characteristically liberal because unlike movie makers who appeal to the general audience, comic writers only have to cater to small niches.

Take Mike Millar, famously subversive comic writer whose work was adapted into “Captain America: Civil War.” He first introduces the national surveillance topic via the Superhero Registration Act. It called for all superheroes to reveal their identities. Through Captain America, he vehemently advocates for the privacy of citizens and against national surveillance.

Another reason that Marvel portrays anti-interventionist sentiments is that it wants to excel in global box offices and hence has to acknowledge the mainly negative global sentiment around the US1.

“Captain America: Winter Soldier” came out at the height of ISIS’s power, when the US was intensifying drone strikes in Iraq. The directors—the Russo brothers—shared in an interview that they wanted to comment on “drone strikes, the president’s kill list and preemptive technology.”2

They did this by pitting our American hero (Captain America) against the Helicarriers—a drone program uncannily similar to the US’s predictive drone strikes. In the film, Captain America questions the justice of the program (“I thought the punishment usually came after the crime”.) By having the Helicarriers target stereotypically American targets–father and son in backyard, White House, Pentagon), Marvel humanizes drone targets. It is a damnation of drone strikes which worked only because they were dehumanizing.

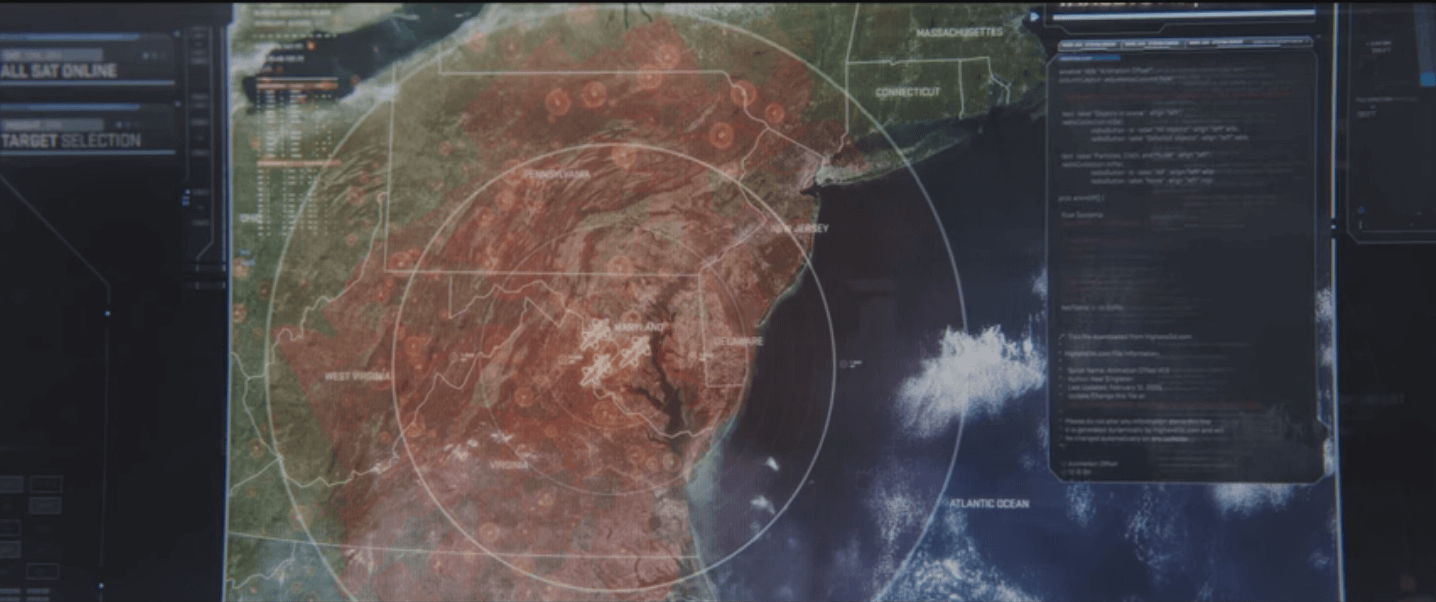

The several thousand targets that the helicarriers plan to kill. The names of US states are prominently displayed.

The several thousand targets that the helicarriers plan to kill. The names of US states are prominently displayed.

In “Captain America: Civil War”, the Russo brothers wanted to question the accountability of US military actions.3 They said in an interview: “We live in a country where we do go over borders all the time and we do what we feel is necessary…There’s still a cost to it.”

So, they turned the conflict international. In the film, the Avengers—an allegory for the US military—had caused so much damage in foreign countries (Nigeria and fictional Sokovia) that the UN wanted to regulate them. The brothers, ironically via the US Secretary of State, delivers scathing critiques of US forign policy. He asks: “What would you call a group of US based, enhanced individuals who routinely ignore sovereign borders and inflict their will wherever they choose and who, frankly, seem unconcerned with what they leave behind?’” He censures the US military for operating with unlimited power and not respecting international norms.

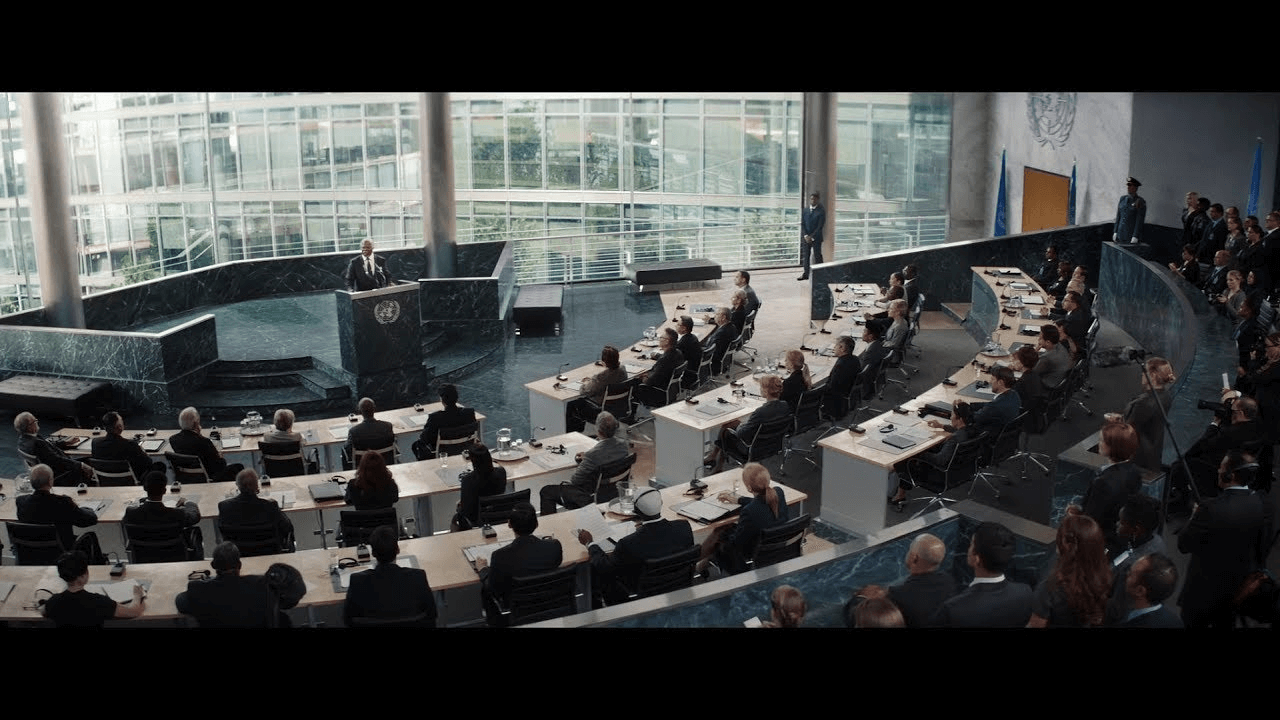

The UN passes the resolution to regulate the Avengers.

The UN passes the resolution to regulate the Avengers.

On the surface, these anti-interventionist critiques may seem scathing. For years, I thought that MCU was highly progressive and anti-imperial. But looking back at these films, I realize that every time Marvel levies an anti-US critique, it undercuts itself. It hijacks the critique via convenient plot diversions. Worse, it attributes the problems to literal Nazis or corrupt individuals, thereby brushing off structural issues as individual flaws.

The drone strikes in “Captain America: Winter Soldier” supposedly ordered by the US government? Oh, plot twist! Well actually that wasn’t the real government—it was the government that was infiltrated by literal Nazis4!

The very important Sokovia Accords that split the Avengers into half? Well actually, the real reason that the Avengers were fractured was a personal beef between Cap and Ironman about Bucky. And by the end of the movie, everyone forgets about the Accords.

Tony Stark’s weapons circulating amongst terrorists abroad? Actually they were only threatening because Stark’s greedy business partner had ordered them to kill him. Also, Stark’s pivot away from weapons turned out to be a huge financial success!

Stark created terrorists Helmut Zemo, and enemies Pietro and Wanda Maximoff because his weapons killed their parents? Actually, Zemo was secretly a Nazi and murderer so don’t worry about him. Also, Wanda happened to work for pure evil, and so she gave up her lifelong vendetta in a blink of an eye and forgave the Avengers.

In each of these examples, an underlying structural issue is blamed on individuals or ignored. We never grapple with the US drone program, the substantive debate on superhuman control, US weapons ending up in enemies’ arms or the creation of terrorists. Instead of interrogating the morality of drone programs and questioning when they are justified, the audience is led to think “Drone programs are good if a good guy has the button.” Instead of addressing the incentives that brought US weapons into terrorists’ hands, we think “if a good guy makes the weapons, that wouldn’t happen again.” Marvel not only ignores its anti-interventionist criticism, but it also trivializes the underlying structural problems.

Perhaps Marvel movies cannot afford to be that progressive because Marvel’s catering to the general demographic. And as much as Marvel wants to reach the global audience, it has to maintain its grip on its US market (which makes up 75% of its profits). Perhaps it is a matter of government funding5. The military and government fund the movies and would only fund scripts that are pro-American.

Either way, it’s important to critically interrogate the Marvel Cinematic Universe’s commentary. I used to see them as progressive films that used the power of aesthetics to move people to fight against imperialism. But now I see that they neuter their critiques. I start to see that a watered down critique could be more dangerous than no critique at all. For a watered down critique placates the audience, absolves Marvel from tackling the big questions, and even conditions the audience to subconsciously equate structural issues to individual problems. When you start seeing MCU films as The Unwilling US Foreign Policy Pundit, you’d realize we have a ways to go before popular film levies balanced critique of US foreign policy.

Notes

Marvel Studio’s President Kevin Feige was asked how anti-US sentiments will affect the film’s box office. ↩︎

Suebsang, Asawin. “Captain America: The Winter Soldier” Is About Obama’s Terror-Suspect Kill List, Say the Film’s Directors. ↩︎

Yu, Mallory. ‘Captain America: Civil War’ Captures Politics Of The Moment. ↩︎

Technically, it was Hydra. But Hydra is a successor organization to the Nazi party. ↩︎